The concept of a design movement which speaks and listens to all parts of society challenges a lot of what we might think of about art and design, and who it is for. It means that space can be designed with the needs and interests of many people in mind. It is a collaborative process which brings the community into design, and design into the community.

It is essential to think about the process of design in the modern world as something not only for an exclusive group of people, or for trained designers to be in control of, but something which will be part of a diverse world. Participatory design uses affordable materials to create art which works for the majority. It is an approach to design which gets people together sharing ideas.

Participatory design is a collaboration between artists and citizens. It is a kind of social democracy which values different viewpoints and experiences as part of the creative process. For example, the Kulturklammer group’s project in Belgrade where residents of the city took part in a workshop to share their memories and personal histories of the city -the public space which connects them – to create a ‘remembrance map’ and ‘revive the spirit of Belgrade’. The idea of creating solidarity between the people is just as important as the design. The participation means that individuals feel involved and that the work belongs to them.

‘Assemble’s working practice seeks to address the typical disconnection between the public and the process by which places are made.’

Many modern art/design/architecture groups are using this approach to bring together communities and interact with them to create projects which are useful and meaningful. The results are often more innovative because they bring together different types of people rather than just designers. Another example is Earsay, who work with people from many different social groups to build bridges between the arts, and between many types of people.

Bibliography

Assemble (2016) Info Available at: http://assemblestudio.co.uk/?page_id=48 Accessed February 2016

Earsay (2016) News and Events Available at: http://assemblestudio.co.uk/?page_id=48 Accessed February 2016

KultureKlammer (2016) Memory Archive of Belgrade Available at: http://www.kulturklammer.org/view/154 Accessed February 2016

Schuler, D. and Namioka, A. ed. (1993) Participatory Design: Principles and Practices New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Simonsen, J and Robertson, T. ed. (2013) Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design New York: Routledge

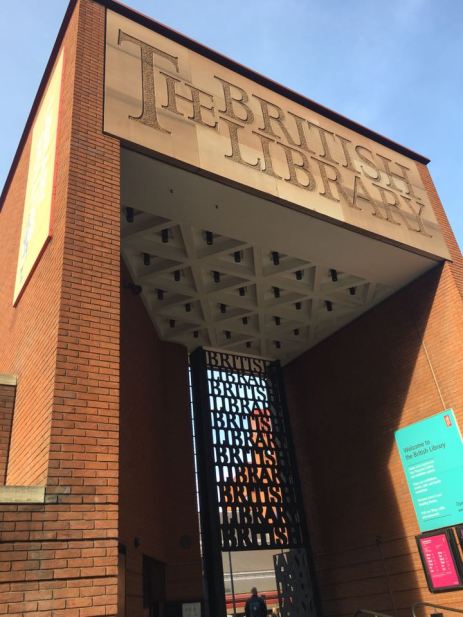

Hanging Lights

Hanging Lights

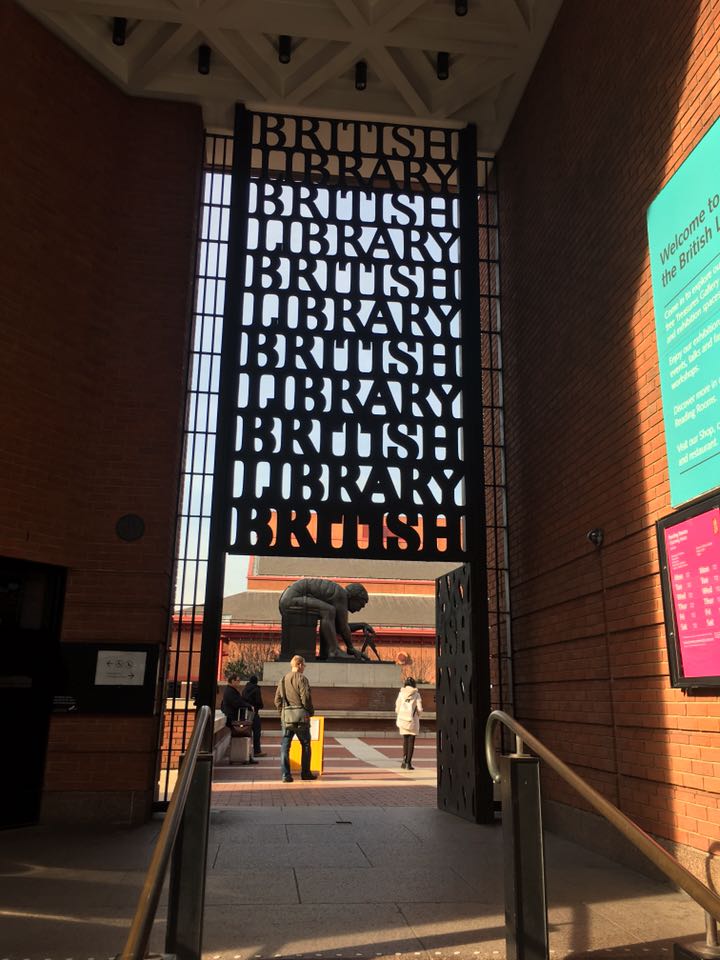

The red brick wall comes to life

The red brick wall comes to life  a wider view looking up

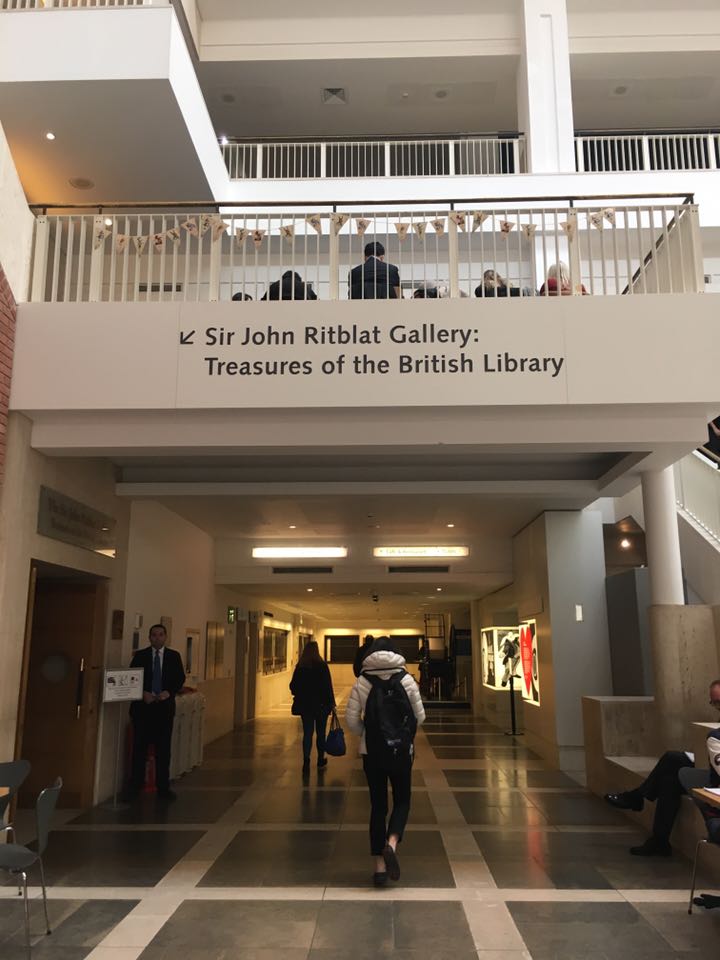

a wider view looking up  open space, light looking down

open space, light looking down alice in wonderland exhibition in black white and red

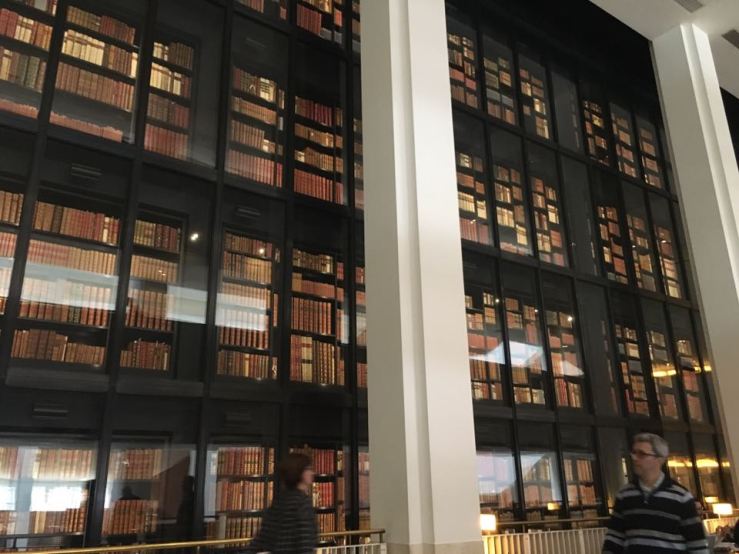

alice in wonderland exhibition in black white and red  wall of books

wall of books